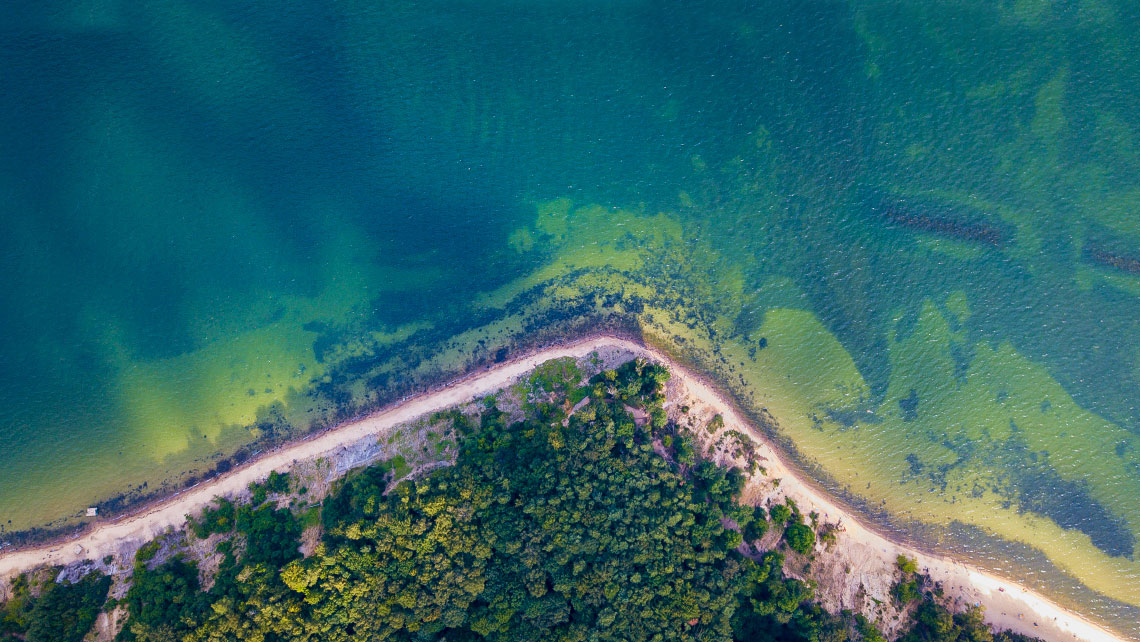

Algae blooms can ruin a good time. They also impact the economy by drying up tourism revenue, destroying aquatic food production and harm our drinking water supply. UNESCO estimates that marine and freshwater algae blooms cause annual economic losses worth several billion U.S. dollars (UNESCO 2015). Not only that – they affect biodiversity. Water with a lot of algae can’t sustain much other life, creating giant dead zones. A 2008 study reports more than 400 dead zones globally.

Algae blooms and the resulting dead zones have one cause: an excess supply of nutrients in the water. Nutrients may sound like a good thing, but not for controlling algae. Excess nutrients come from agricultural fertilizer and domestic wastewater that get flushed into our lakes and rivers, or out to sea. Sewage water contains a lot of nitrogen and phosphorus which, if not adequately removed in sewage treatment plants, end up where people (and other living things) like to swim. There these nutrients literally fertilize algae and other aquatic plants that grow uncontrollably and endanger biodiversity. It’s called eutrophication. Climate change is making it worse because the problem grows in warm water.

Some fertilizer can be reused but not once it’s flushed into our rivers, lakes and seas.

“Despite recent steps in the right direction, I am still concerned” says Rasmus Valanko, Sustainability Director at Kemira, “Let’s just take the Baltic Sea as an example. It is shallow sea with relatively large drainage area. Excess nutrients entering the ecosystem have led to more frequent harmful algal blooms, and a larger dead zone on the seafloor than would naturally occur – almost twice the size of Denmark. Humans have impaired the ecosystems natural capacity to function.

Despite recent progress in the treatment of municipal wastewater, over-fertilization in agriculture still remains a challenge. “As a society, we are still dumping large amounts of phosphorus and nitrogen into the Baltic Sea through our wastewater,” he explains. “This has direct consequences on both the health of the environment, and knock-on effect on us as a society. It is also financially wasteful as some fertilizer can be reused but not once it’s flushed into our rivers, lakes and seas. This situation clearly contradicts the idea of a circular economy and the new EU Green Deal,” Valanko adds.

Wastewater treatment plays a crucial role in solving the problem

It is possible to fix the problem. Based on the latest findings from the report “State of the Baltic Sea” by the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission, also known as the Helsinki Commission or HELCOM. The Gulf of Finland is a good example of how effective modern wastewater treatment technology can protect our waters from over-fertilization. Phosphorus input to the Gulf has been cut by more than half thanks to improved wastewater treatment in St. Petersburg, Russia, as well as the prevention of phosphorus release from a fertilizer factory in nearby Luga. It’s a step in the right direction, but reversing algae blooms takes time and the progress isn’t yet visible. According to HELCOM, eutrophication in the Baltic Sea will continue to impact biodiversity and human well-being for now.

Full recovery in the region, and in other places where eutrophication is an issue, depends on sustained efforts over the long term. Usually it takes cooperation from several different groups. By working together, the government, the agricultural industry and wastewater treatment utilities can make the circular economy a reality. They can implement modern wastewater treatment solutions to remove excess nutrients and reuse them instead of letting nutrients end up where we swim. That would help restore our waters, improve biodiversity and make sure happy beachgoers can take full advantage of summer days by the sea.